Author: Mycond Technical Department

Optimising capital expenditure on air dehumidification systems is becoming a critically important task for industrial facilities in the UK, especially given the humid climate of cities such as London, Manchester and Glasgow. The classic conflict between capital costs (first cost) and operating costs in dehumidification projects requires careful balancing. The basic principle of minimising capital costs is to remove only the minimally necessary amount of moisture in the most efficient way.

Neglecting proper dehumidification carries a high opportunity cost: equipment corrosion worth tens of thousands of euros, production downtime up to 5000 euros per day, loss of product quality. Given that the typical service life of dehumidification equipment is 15-20 years, the cumulative effect of system optimisation can far exceed the initial investment many times over. The economic benefits fall into four categories: reduced operating costs, reduced capital investment in other equipment, improved product quality and increased operational flexibility.

Minimising moisture loads as the basis for reducing capital costs

A fundamental dependency in dehumidification system design: the size and cost of the system are directly proportional to the moisture load. Reducing the load by 50% can cut capital costs by 50-60%. For effective design, it is important to understand the hierarchy of sources of moisture load in a typical industrial space:

- Open doors and loading bays: 50-70%

- Supply (ventilation) air: 15-30%

- Infiltration through gaps: 5-15%

- Conveyor and process openings: 3-8%

- Breathing and evaporation from people: 2-5%

- Vapour permeability through the building envelope: 1-3%

Consider an example of a cold store at -18°C. With a practice of opening loading bay doors for 3 minutes for each truck in/out (15 cycles per hour), the moisture load is about 135 kg/h of water vapour. This requires a dehumidifier with an airflow of over 15000 m³/h. Reducing the opening time to 1 minute lowers the load to approximately 20 kg/h (airflow 2500 m³/h) — an 85% reduction, allowing the use of a dehumidifier six times smaller in capacity and cost.

Effective methods to reduce door-related loads include:

- High-speed roll-up doors (opening time under 3 seconds) — 40-60% load reduction

- Air curtains with flow velocity 8-12 m/s — 30-50% reduction

- Airlocks with a volume of 15-30 m³ — 60-80% reduction

- PVC strip curtains — 20-40% reduction

Infiltration through gaps has a much greater impact on the moisture load than wall vapour permeability. A gap 1.5 mm wide and 1 m long at a pressure differential of 10 Pa passes about 50 g/h of moisture, whereas 50 m² of a painted 200 mm concrete wall passes only 5-8 g/h.

Optimising control levels and tolerances

The cost of a dehumidification system rises exponentially with the depth of drying. With an internal load of 5 kg/h of water vapour, to maintain a dew point of +5°C (humidity ratio 5.4 g/kg) an airflow of around 1200 m³/h is needed. For a dew point of -10°C (humidity ratio 1.8 g/kg) already 3500 m³/h is required, and for a dew point of -25°C (humidity ratio 0.5 g/kg) — over 12000 m³/h. This is a tenfold increase when lowering the dew point by only 30 degrees.

The “dry enough” principle involves defining the minimally required humidity level that delivers the process outcome without excessive margin. Ambiguous specifications often lead to overspend. For example, the brief requires a humidity ratio of 2 g/kg ±0.7 g/kg but does not specify the measurement location. Control at the diffuser outlet requires a dehumidifier with 10 kg/h capacity, whereas a requirement for a uniform humidity ratio throughout a 500 m³ room with a deviation no more than 0.7 g/kg between any two points requires a system with 8000-10000 m³/h airflow and 25-30 kg/h capacity.

Pre-dehumidification of supply air

Outdoor air is often the dominant source of moisture. In a typical industrial space controlled at a dew point of -10°C with ventilation at 2000 m³/h, supply air under summer conditions (30°C, 18 g/kg) brings in about 43 kg/h of moisture, which may constitute 70-90% of the total load.

An effective strategy is deep dehumidification of ventilation air before mixing with recirculated air. Calculation example: outdoor air at 32°C and 21 g/kg, when dried by a desiccant to 1 g/kg, yields a drying capacity of 20 g per kilogram of dry air. At 1000 m³/h (air density 1.15 kg/m³) this allows removal of up to 23 kg/h of internal moisture, sufficient for a room of 500-800 m².

Additional economic benefit is achieved by pre-cooling the supply air before desiccant dehumidification. Cooling from 32°C to 12°C (dew point) reduces the humidity ratio from 21 to 9 g/kg, i.e. removes 57% of the moisture by the cheaper refrigeration method (removal cost 0.8-1.2 euros/kg of moisture), leaving only deep post-drying for the desiccant (cost 1.5-2.5 euros/kg).

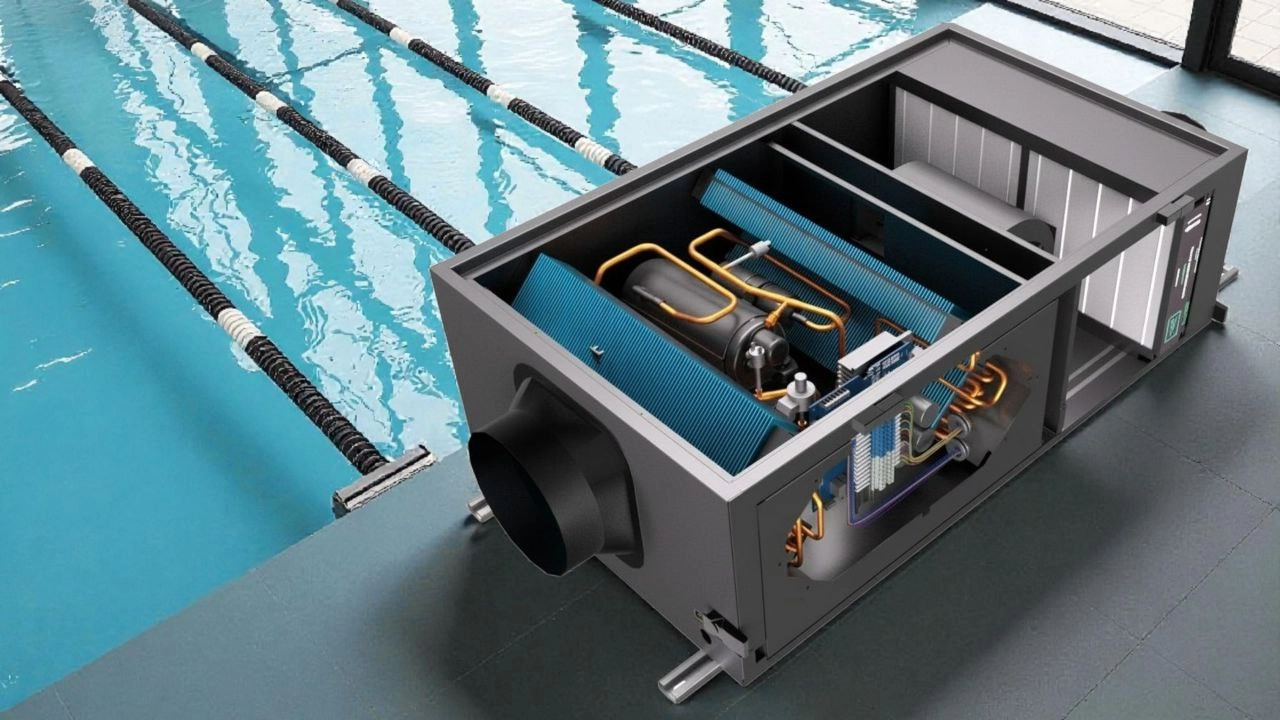

Combined systems of cooling and desiccant dehumidification

The load-splitting principle according to technology efficiency is to use refrigeration condensing dehumidification at dew points above +8...+12°C (humidity ratio over 6-8 g/kg) and desiccant adsorption at dew points below +8°C. The physical reason: at low dew points the evaporator of a refrigeration unit operates at +2...+5°C with a COP of only 2.0-2.5 and a risk of frosting, whereas a desiccant has no temperature limitations and its effectiveness even increases with deeper drying.

Typical combined system configurations:

- Desiccant dehumidification of supply air only — used with small internal loads up to 5 kg/h and large supply flows over 3000 m³/h. Advantages: simplicity and low capital cost. Drawback: limited capacity.

- Pre-cooling of supply + desiccant dehumidification of mixed air — the most common option for dew points from 0 to -15°C and loads of 10-50 kg/h with an optimal cost balance.

- Mixing, cooling, then desiccant dehumidification — for systems with high energy efficiency requirements and access to cheap chilled water at 6-8°C.

- Fully desiccant system — used when free waste heat for regeneration is available or when a high supply temperature level of 35-45°C is acceptable.

A properly designed combined system can be 25-40% cheaper in capital costs and 20-35% more economical in operation compared to a single-technology solution for dew points in the range of -5...-20°C.

Typical design mistakes and their economic consequences

Eight common mistakes that significantly increase capital costs:

- Excessive capacity margin of 50-100% — leads to operation at 30-50% load with a COP 20-30% lower and capital costs inflated by 40-80%.

- Ignoring operational factors — calculating based on existing door-opening practices without attempting optimisation can inflate the load by 50-200%.

- Over-specifying the dew point — requiring -40°C when -25°C is sufficient for the process increases system cost by 2-3 times.

- Strict tolerances without justification — requiring ±0.3 g/kg instead of ±1.0 g/kg can double airflow and system cost.

- Choosing only one technology — using desiccant-only dehumidification for a +5°C dew point where refrigeration would be 40% cheaper.

- Ignoring pre-cooling — feeding hot, humid air directly to the desiccant increases the desiccant block size by 60-80%.

- Overemphasis on vapour permeability — investing in expensive membranes while service penetrations remain unsealed.

- Lack of power modulation — a system without a variable frequency drive (VFD) runs on on/off control with 25-40% energy overspend.

Operational and organisational factors

Doorway management should be a systematic approach: develop procedures for staff with a requirement to close doors within 60 seconds, install visual signalling after 30 seconds and audible after 60 seconds from opening, and design airlocks with a volume of 20-40 m³.

System modularity ensures efficient operation: a base system sized for 70% of typical load with an additional module of 40-50% for peak periods allows the main equipment to operate at a high utilisation of 80-95%.

Regular maintenance is critical: replace filters every 2-3 months (a dirty filter increases pressure drop by 50-150 Pa), lubricate fan bearings every 6 months, and check ductwork tightness annually. The cost ratio of preventive maintenance to emergency repair with production downtime is typically 1:10.

FAQ: The most common questions about optimising capital costs

What does the capital cost of a dehumidification system depend on most?

The capital cost of a dehumidification system depends most on two factors: the moisture load in kg/h and the target dew point in °C. Reducing the moisture load by 30% typically lowers system cost by 25-35%. Changing the dew point requirement has an even more dramatic effect: moving from a -5°C to a -25°C dew point increases system cost 3-4 times due to the need for higher airflow and deeper drying.

Is it always economically justified to reach the deepest possible dew point?

Achieving an excessively deep dew point is rarely economically justified. Costs rise exponentially: a system to maintain a -30°C dew point will cost roughly twice as much as a system for -20°C at the same load. The “dry enough” principle involves determining the minimum level that meets process requirements. For most industrial processes, including pharmaceutical manufacturing and the electronics industry, a dew point of -20°C is sufficient, and going deeper only increases capital and operating costs without noticeable process benefit.

How do you determine whether it is more cost-effective to invest in sealing the room or in a more powerful dehumidifier?

To decide, compare the one-off sealing costs with the additional capital and operating costs of a more powerful dehumidifier over 3-5 years. Example: sealing gaps in a 1000 m² cold store costs 3500-4500 euros and reduces the moisture load by 25 kg/h. This allows a reduction in dehumidifier power by 15 kW, cutting capital costs by 25000 euros and operating costs by 6000-8000 euros/year. The payback period is less than 6 months, making sealing a much more advantageous investment.

Conclusions

Optimising capital expenditure on air dehumidification systems requires a systematic approach:

- Reduce the load through sealing and door management

- Optimise the control level to the minimally necessary

- Select the optimal combination of technologies

Key questions for the design engineer: what is the real (not inflated) load? What is the minimally acceptable humidity level? Can the load be reduced by organisational measures? What is the cost of thermal energy for regeneration? Are there sources of waste heat?

The greatest economic impact comes from the simplest measures: sealing gaps and staff procedures. A dialogue between the designer, the client and the operations team is critically important for a realistic assessment of loads and to avoid both under- and over-specification of system parameters.