Author: Mycond Technical Department

The air around us is not just a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen; it is a complex system containing water vapour, the state of which directly affects human comfort, building energy consumption and the longevity of structures. Understanding humid-air parameters is fundamental to professional HVAC practice: without it you cannot correctly size equipment, prevent condensation on cold surfaces or ensure an optimal indoor microclimate. That is why every specialist in heating, ventilation and air conditioning should master the properties of humid air and be able to apply them in practice.

Dry-bulb temperature

Dry-bulb temperature (T) is the ordinary air temperature measured with a thermometer in degrees Celsius (°C). It is called “dry” to distinguish it from wet-bulb temperature, discussed later. It is the most intuitive parameter we feel and the one we use to set heating or air-conditioning systems.

Comfort set-points for dwellings are 20–22°C in winter and 23–25°C in summer. For office spaces, 21–23°C are considered optimal. On a , dry-bulb temperature is plotted on the horizontal axis, which makes it easy to track changes in this parameter.

Relative humidity

Relative humidity (RH or φ) is the percentage of the maximum possible water vapour content at a given temperature. It is measured in percent (%) and is a key parameter for assessing human comfort. A crucial feature of relative humidity is its dependence on air temperature.

For example, winter air at -5°C and 80% RH, after being heated to +21°C, will have a relative humidity of only about 20% at exactly the same amount of water vapour. This is why air often feels dry in British homes during the heating season.

Values of 40–60% are considered comfortable for people. Below 30% problems with drying of mucous membranes begin, and above 70% there is a feeling of stuffiness and impaired heat rejection by the body. On a psychrometric chart, relative humidity lines are curved.

Humidity ratio

Humidity ratio (d, w or x) is the actual physical amount of water vapour contained in air. It is measured in grams per kilogram of dry air (g/kg). Its main advantage is that it does not depend on temperature and shows the true amount of moisture.

Typical humidity ratio values: for a dry winter day – 2–4 g/kg; for comfortable indoor conditions – 6–9 g/kg; for a humid summer day – 12–18 g/kg; for a tropical climate – over 20 g/kg.

Humidity ratio is a key parameter for calculating the moisture removed by dehumidification systems. The amount of removed moisture is calculated as the product of airflow and the difference in humidity ratio before and after the dehumidifier: G = L × (d1 - d2). On a psychrometric chart, lines of constant humidity ratio are horizontal.

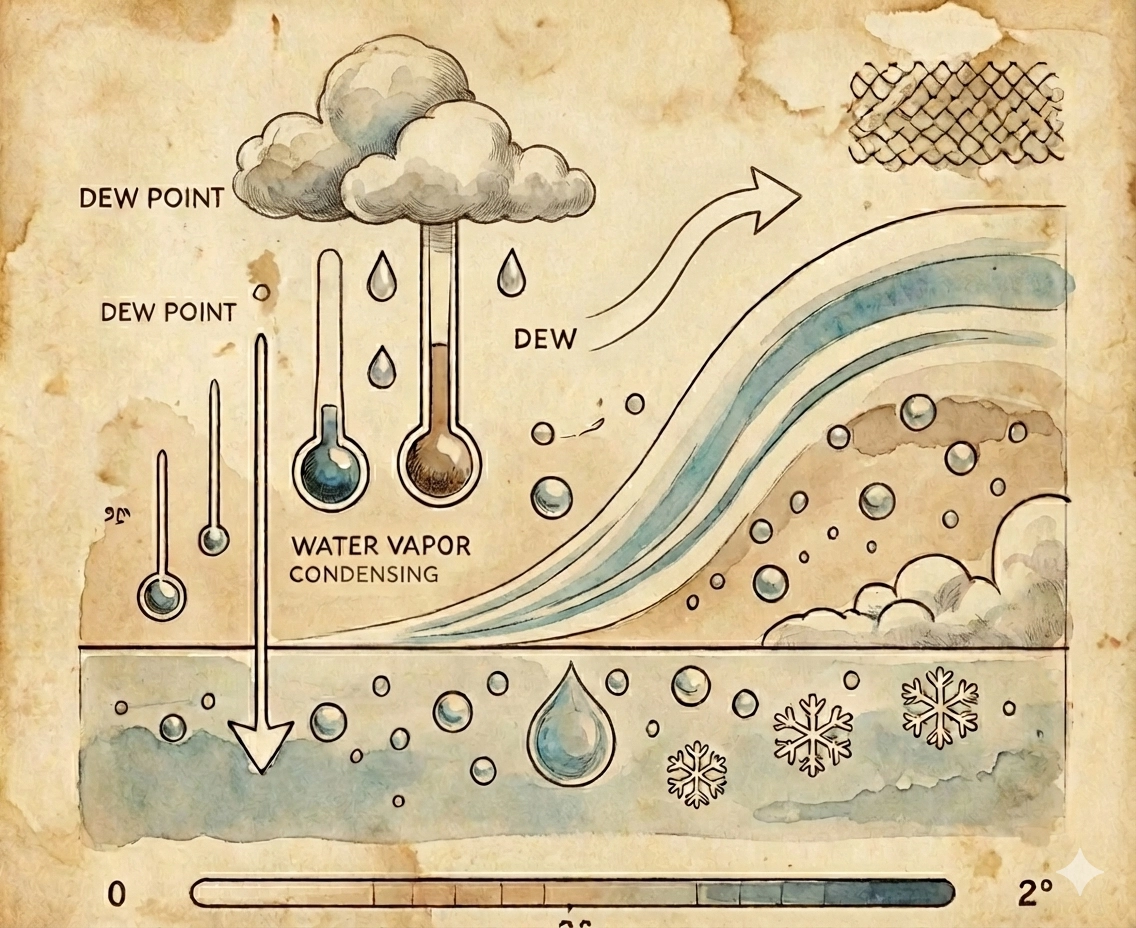

Dew-point temperature

Dew-point temperature (Td) is the temperature at which air reaches saturation (100% relative humidity) and condensation begins. It is measured in degrees Celsius (°C). The physical meaning is: if the temperature of any surface drops below the dew point, condensate will form on it.

A classic example is a glass of cold water “sweating” in a warm room. For instance, in a room at 21°C and 50% relative humidity, the dew point is about 10°C. This means condensation will occur on surfaces with temperatures below 10°C.

Situations are especially critical on windows in winter and within the wall build-up, where hidden (interstitial) condensation can form. Practical recommendation: keep surface temperatures at least 2–3°C above the dew point. On a psychrometric chart, dew point corresponds to the left vertical of the saturation line.

Partial pressure of water vapour

The partial pressure of water vapour (pv) is the pressure exerted by water molecules in the air. It is measured in pascals (Pa) or kilopascals (kPa). Physically, each water molecule in the gaseous state “pushes” on its surroundings, creating a certain pressure.

Partial pressure is particularly important for understanding moisture diffusion through walls, since moisture moves from regions of higher vapour pressure to lower. For example, in winter a significant pressure difference between a room (approximately 1200–1500 Pa) and outdoors (300–400 Pa) “drives” moisture through the wall. That is why correct vapour control design is critical for buildings in the UK’s humid climate.

On a psychrometric chart, the scale of the partial pressure of water vapour is on the right, parallel to the humidity ratio scale, because these parameters are related.

Enthalpy

Enthalpy (h or i) is the total energy of humid air, comprising sensible heat (associated with temperature) and the latent heat of water evaporation. It is measured in kilojoules per kilogram (kJ/kg). This parameter is critically important for energy calculations in air-conditioning systems.

For example, air at 21°C and a humidity ratio of 7.8 g/kg has a total enthalpy of about 41 kJ/kg, of which approximately 21 kJ/kg is sensible heat and 20 kJ/kg is latent heat. It is important to remember that evaporating 1 kg of water requires about 2500 kJ of energy.

The capacity of an air-conditioning system is calculated as the product of mass airflow and enthalpy difference: Q = L × ρ × (h1 - h2), where L is volumetric airflow (m³/s), ρ is air density (kg/m³). On a psychrometric chart, lines of constant enthalpy are diagonal, with the scale at the top left.

Wet-bulb temperature

Wet-bulb temperature (Tw) is the temperature to which water cools when it evaporates into unsaturated air. It is measured in degrees Celsius (°C). Physically, it is the temperature indicated by a thermometer wrapped in a wet wick as air flows past it—evaporation removes heat and cools the thermometer.

For a space at 21°C and 50% relative humidity, the wet-bulb temperature is about 15°C. In the limiting case of 100% relative humidity, evaporation is impossible and wet-bulb temperature equals dry-bulb temperature.

This parameter is traditionally used for simple humidity measurements with a sling psychrometer, but more importantly for assessing the potential of evaporative cooling. For example, at 35°C and 30% relative humidity the wet-bulb temperature is about 22°C, which means cooling of roughly 10–11°C is possible without mechanical refrigeration, purely through water evaporation. This principle is applied in cooling towers and adiabatic humidification systems.

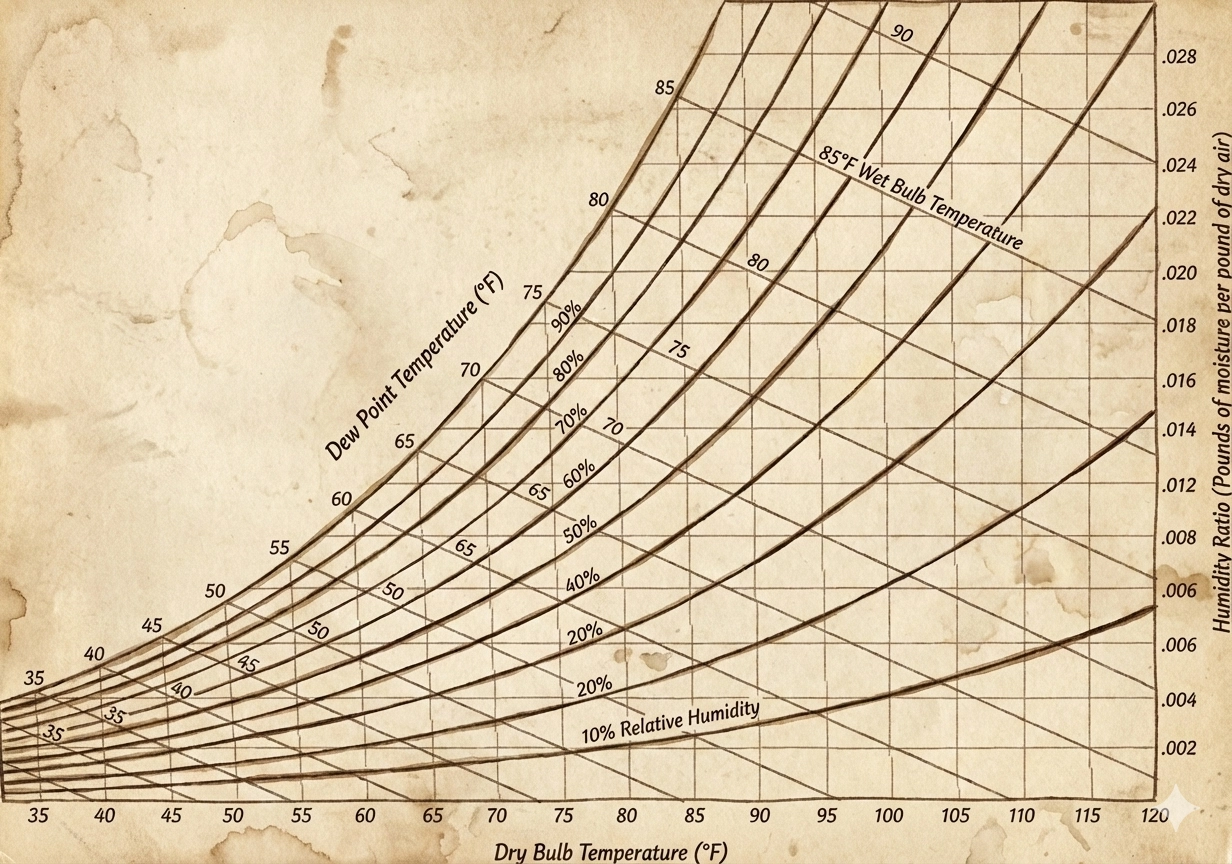

Psychrometric chart

The is a graphical tool that links all seven humid-air parameters. Its main advantage is that, knowing any two parameters, you can determine all the others. The most commonly used combinations are:

- Dry-bulb temperature + relative humidity – the easiest parameters to measure;

- Dry-bulb temperature + dew point – for condensation control;

- Dry-bulb temperature + humidity ratio – for air dehumidification calculations.

Let’s consider a practical example of using the psychrometric chart: cooling outdoor air from 32°C and 70% RH to 22°C. Determine the initial parameters: the humidity ratio is approximately 22 g/kg and the enthalpy is 89 kJ/kg. After cooling to 22°C the air will be supersaturated, so some moisture will condense, and the humidity ratio will drop to about 16 g/kg while enthalpy falls to 63 kJ/kg. The amount of condensed moisture will be 6 g for each kilogram of processed air, and the air-conditioner capacity will be determined as Q = L × ρ × (89 - 63) = L × ρ × 26 kJ/kg.

Common mistakes and their consequences

The most common mistakes when working with humid-air parameters are:

- Equating relative humidity with the absolute amount of water in the air;

- Ignoring the change in relative humidity when heating air;

- Underestimating vapour pressure differences when designing vapour control layers;

- Neglecting latent heat in energy calculations.

These mistakes lead to serious operational consequences: condensation on windows and pipes, moisture accumulation in walls, incorrect equipment sizing and occupant discomfort. This is especially critical for the humid climate of the United Kingdom, where proper humidity management is of primary importance.

Frequently asked questions about humid-air parameters

Why is indoor air dry in winter even when outdoor humidity is high?

This is due to the relative nature of humidity. Cold outdoor air, say at -5°C and 80% relative humidity, contains only about 2.5 g/kg of moisture. When heated to 21°C without additional humidification, its relative humidity drops to 20%, creating a feeling of dryness.

How can I quickly estimate the dew point without instruments?

You can make a rough estimate using this rule of thumb: at room temperature (around 20°C) and normal humidity (50%), the dew point is roughly 10°C below the air temperature. As humidity decreases the difference increases; as it rises the difference decreases.

What is latent heat and why is it important?

Latent heat is the energy associated with the phase change of water between liquid and vapour. When 1 kg of water evaporates, about 2500 kJ of energy is absorbed, which is then released during condensation. In air-conditioning systems latent heat can account for up to 50% of the total cooling load, so ignoring it leads to serious calculation errors.

How does humidity ratio differ from relative humidity?

Humidity ratio (g/kg) shows the actual amount of water vapour in the air and does not depend on temperature. Relative humidity (%) shows how saturated the air is with water vapour relative to the maximum possible at a given temperature and is strongly temperature-dependent.

Why use humidity ratio for dehumidification calculations rather than relative humidity?

Because humidity ratio shows the actual mass of water that must be removed. A dehumidifier removes a specific mass of water, not “percent humidity”. The difference in humidity ratio before and after the dehumidifier allows an accurate calculation of the condensed moisture.

Conclusions

Each of the seven humid-air parameters has its practical value for HVAC engineers:

- Dry-bulb temperature – the basis for providing thermal comfort;

- Relative humidity – an indicator of comfort and a favourable environment for material preservation;

- Humidity ratio – the fundamental parameter for dehumidification and humidification calculations;

- Dew-point temperature – the key to preventing condensation and related problems;

- Partial pressure of water vapour – the basis for vapour control design;

- Enthalpy – fundamental for energy calculations and equipment capacity assessment;

- Wet-bulb temperature – an indicator of evaporative cooling potential.

A deep understanding of the relationships between these parameters enables engineers to make informed decisions that ensure an optimal indoor climate, energy efficiency and building durability—especially in the humid British climate.